A Close-up of Costume Embroidery and Designs. Click to go to Costume Page.

Music

About Cantonese Opera

This page co-authored by Stacey Fong and Erick Lee.

Cantonese

Opera is a traditional

Chinese art form that involves music, singing, martial arts, acrobatics, and

acting. Cantonese Opera plays tell stories about Chinese history,

traditions, culture, and philosophies.

Cantonese

Opera Costumes

A Close-up of Costume Embroidery and

Designs. Click to go to Costume

Page.

Music

Cantonese Opera music

consists of innumerable melodies and tunes. Unlike European opera where

the composer of the music is praised, in Cantonese opera the music isn’t the

most important part - the lyrics are. In

Cantonese opera the writers put words into this pool of melodies and tunes.

One song may contain many melodies, and it is up to the singer to add his

or her own personal variation and style to the melody when they sing it.

The singing must be combined with music, of course. Traditional Chinese

instruments such as the er wu (yee wu), butterfly harp, pay-paa, flute, and

percussion, to say the least, make up the Cantonese Opera orchestra. The

percussion alone consists of many different drums and cymbals. The

percussion is responsible for the overall rhythm and pace of the music, while

the er wu leads the orchestra. Now,

Cantonese opera has incorporated many western instruments such as the cello,

saxophone, and even the violin which is often used in place of the er wu.

Types of Plays

There are two types of Cantonese Opera plays.

One is called "Mun," and the other is called, "Mo."

Mo means martial arts. Characters in Mo

plays are usually generals or warriors. Mo plays are action-packed

and intricately choreographed, often using weapons. The costumes for Mo

plays are very complicated (and heavy).

Mun means intellectual, polite, cultured.

These are the plays whose characters are either scholars, royalty. Mun plays

tend to be dramatic and the movements are soft and slow. Instead of using

weapons, performers show of their abilities in water sleeves work (see terms

below). This type of play focuses more on facial expression, tone of

voice, and meaning behind the movements.

While actors are singing and moving around on stage, they also have to

act! Cantonese opera acting is not the same as acting in movies or on TV.

Many emotions have certain facial expressions and body gestures that go along

with it. Performers also have to be careful not to ruin their makeup or

hair with histrionic expressions.

Makeup

Cantonese Opera makeup is very unique and

difficult to master. For the most common type of makeup, the white and red

face, the process is as follows. First,

a white or off-white base foundation is applied to the entire face, including

the neck and ears. Then, red rouge is spread across the eye area, blending

down to the cheeks and stopping just at the bridge of the nose.

Traditionally, the eyes and eyebrows are drawn following the natural shape.

Nowadays, the eyebrows must be drawn at a sharp, upward angle, and the

eyes are also drawn slanting upwards, to make them appear long. The actor

gives the eyes and eyebrows a lift using a flat black ribbon and pulling the

skin tightly upward and tying it tightly behind the head.

Some actors, now, prefer to use cosmetic tape to pull their eyes into a

slant, to lessen the discomfort, and it does make eyelining easier.

Lipstick is bright red. The

makeup helps enhance the actor’s facial features and many times tells the

audience a lot about the characters personality. For instance, if an actor plays a comical role, he will

usually paint a large white circular shape in the center of his face.

This tells the audience that he is a comical character.

If the character in an opera is ill, the actor playing that role paints a

thin red line in between the eyebrows upward, symbolizing sickness.

For male generals or male characters with a lot of aggression, the actor

paints a “ying hong jee” in

between his eyebrows. This is an

arrow shape that is painted and blended starting from between the eyebrows and

fading into the forehead. This

symbolizes a lot of frustration in the character.

|

|

Actor Ding Faan as a male general, with ying hong jee on his forehead. From Chinese Opera. See reference page for book details. |

Closeup of female general. From Chinese Opera. See reference page for book details. |

There is also another type of face painting which

is always associated with Chinese opera. This

type is called “hoy meen” which

literally translates to open face. The

characters that wear this type of makeup are tall, broad male characters, such

as the three sworn brothers, in the famous story the

Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Guan Yu, Jueng Fey, and Lao Bey.

This type of makeup is truly an art of its own.

The actor applies many different colors of oil-base and water-base makeup

to create different faces of characters. Each open face character in opera has their own different

makeup. These consist of many

symbols, intricate details, and blending. The

colors used are just as important as the designs because each color also

symbolizes something different.

Pictured: Open Face. From Peking opera. See reference page for book details. |

Open Face with Beard and helmet (dai ngak ji) From Chinese Opera. See reference page for book details. |

Hair

A performer’s hairstyle tells a lot about their

character’s age, status, and abilities.

Men will put on a hat, the design of which depends on their

character. Scholars or government officials have hats with two flaps on

the sides. Soldiers have very simple hats, while generals have large

helmets with pheasant feathers (see terms below). Kings wear crowns.

Pictures of hats can be viewed on the Costumes

Page. Besides hats and helmets, male characters also have hair “styles.”

For a general or warrior that has lost a battle and therefore lost his

helmet, a ponytail-like hairstyle is worn on the top of the head.

The character may swing the long hair in circles showing frustration or

grief (see terms below). Another

type of hairpiece that male roles can wear is a type of wig that has a bun on

the top of the head and hair flowing down the back.

This can be worn by numerous types of characters.

For older characters of opera, the beard is also a very important part of

the role. There are many types of

beards consisting of long or short, and black, white, grey, or even red!

Actor Ngou Hoi Ming demonstrates the pony-tail hairstyle. From the opera Gate of the White Dragon. |

Actor Ding Faan flings his ponytail. From the opera Kneel Thrice, Bow Nine Times (Fan Lay Faa). |

Character with white beard. From Chinese Opera. See reference page for book details. |

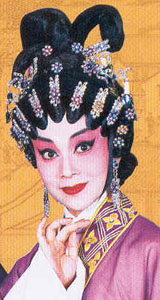

Women have to put on "peen jee," which are like

bangs. After the peen jee comes the larger hairpiece, which is usually a

ponytail that extends down past the waist. Then, the women adorn their

heads with jewelry, flowers, and other hairpieces. The hairstyle will tell

a lot about the woman's status. Women in mo plays almost always

wear helmets with peacock feathers. In Mun plays, the hairstyles

are more diverse. A maid or a young girl usually has her hair done in

buns, with little jewelry. A young, unmarried woman will have her hair

down (in a ponytail), with part of it swept up to one side, and jewelry and

flowers (more if she is rich). A married woman has two hairstyles: one is

called dai tow (literally, big head), where the woman has two very long

strands in the front, and the rest bound up and covered with jewels. The

other style is similar to an unmarried woman's, except the ponytail in the back

is tied up at the nape of the neck. Fairies or royalty usually have their

hair left down (in a ponytail), with a very high crown or tiara set in the

middle. If a queen or princess is at a formal party, they will wear what

is called a kwai, which is like a helmet adorned with jewels.

Woman applying Peen Jee. From Chinese Opera. See reference page for book details. |

Actress Chung Wai with dai tow hairstyle. |

Actress Chen Wun Hung with female general's helmet. From the opera Kneel Thrice, Bow Nine Times (Fan Lay Faa). |

Actress Lee Sok Kun with an unmarried girl's hairstyle. From the opera Teen Ngai Fong Cho Fung Chun Hak. |

Cantonese

Opera's Frequently Used Terms

|

Pheasant

feathers/Antennae |

Worn

by both men and women in Mo plays. These are very long

pheasant feathers on the performer's helmet that...well...look like

antennae! The performer uses these feathers to express their

feelings or to display their skill. |

|

Water

Sleeves |

Usually

worn by both men and women, in Mun plays. These are very long

pieces of white fabric connected to the sleeves that, when handled

correctly, are supposed to flow as softly and smoothly as water.

The movements performed by the actor, or actress, with the water

sleeves have a symbolic meaning. |

|

Hand

Movements |

The

shape and position of an actor's hands and fingers will interpret the song

or the scene being performed. Generally, women must hold their hands

in a "lotus flower" position, which is considered softer and

more feminine than straightening all their fingers. |

|

Round

Table/Walking |

Cantonese

opera has very specific movements, and one of the most basic but difficult

is the walking (speed walking), affectionately called the round table.

Women have to take very, very small steps, while their upper bodies float

as if disconnected from their legs. Men can take larger steps but

their upper bodies have to also remain detached from their lower bodies.

This is a graceful movement and symbolizes traveling a long

distance. |

|

Go

Hur |

Opera

shoes worn by men. It consists of a black boot with a thick and high

white sole. This makes round table for men very difficult. The

higher the shoes, the harder the round table and all other movements are! |

|

Gwou

Wai |

A

move in which two performers cross over to opposite sides of the stage. |

|

Tuir

Mok |

A

move in which the two performers walk in a circle facing each other and

return to their original positions |

|

Lai

saan & Wun Sou |

This

is the most basic movement that combines the hands and the arms.

This movement is used in many other more complex moves and is one

of the moves that is taught first to beginners is opera. |

|

Jurt

Bo/Choot Bo |

Used

in Mo or Mun plays by men

and women, this technique is often incorporated into the round table.

It looks like skipping, but the body should glide, not jump. |

|

Siu

Tiu |

Translated

as “small jump,” this movement is generally used in Mo plays. It is

somewhat like a stomp with one foot before starting a round table.

This movement is done smoothly. |

|

Fay

Tuir |

In

regular martial arts terms, it would be called an inside crescent kick. |

|

Hair-flinging/ |

This

movement can be done by both male and female roles, in Mun or Mo plays.

This is where they swing their ponytails in a circle over and over

again. This symbolizes

frustration or grief, such as when a loved one dies in a dramatic way. |

|

Chestbuckle/

Flower |

This

is a spherical flower made from a long length of fabric that is folded a

certain way, tied very tightly, and then shaped into a sphere, similar to

a NordstromÔ

gift box bow. They are worn

by male and female Mo roles as a

decoration on the chest, and also a red flower is worn by a male when

getting married. |

|

Horsewhip |

This

is a prop that people use on stage to symbolize a horse or riding on a

horse. It is a thin piece of

rattan that is about 3 ft. long and is bound with colored silk and

tassels. The actor or actress

swings the whip and starts a round table, which symbolizes riding a

galloping horse. |

|

Sifu |

Literally,

“Master,” this term is used for professional actors (who have been

trained in schools in China). It

is also what opera students call their opera teacher/coach. |

[Home]

[About

Cantonese Opera] [News & Events] [ABC

Corner] [NBC

Corner] [CBS

Corner]

[Editorials] [Spotlight on...] [About

this site]

©

2002-2003 Bay Area Cantonese Opera. All rights reserved.